Landau damping

In physics, Landau damping, named after its discoverer,[1] the eminent Soviet physicist Lev Davidovich Landau, is the effect of damping (exponential decrease as a function of time) of longitudinal space charge waves in plasma or a similar environment.[2] This phenomenon prevents an instability from developing, and creates a region of stability in the parameter space. It was later argued by Lynden-Bell that a similar phenomenon was occurring in galactic dynamics,[3] where the gas of electrons interacting by electro-static forces is replaced by a "gas of stars" interacting by gravitation forces.[4]

Contents |

Wave-particle interactions[5]

Landau damping occurs due to the energy exchange between a wave with phase velocity  and particles in the plasma with velocity approximately equal to

and particles in the plasma with velocity approximately equal to  , which can interact strongly with the wave. Those particles having velocities slightly less than

, which can interact strongly with the wave. Those particles having velocities slightly less than  will be accelerated by the wave electric field to move with the wave phase velocity, while those particles with velocities slightly greater than

will be accelerated by the wave electric field to move with the wave phase velocity, while those particles with velocities slightly greater than  will be decelerated by the wave electric field, losing energy to the wave.

will be decelerated by the wave electric field, losing energy to the wave.

In a collisionless plasma the particle velocities are often taken to be approximately a Maxwellian distribution function. If the slope of the function is negative, the number of particles with velocities slightly less than the wave phase velocity is greater than the number of particles with velocities slightly greater. Hence, there are more particles gaining energy from the wave than losing to the wave, which leads to wave damping. If, however, the slope of the function is positive, the number of particles with velocities slightly less than the wave phase velocity is smaller than the number of particles with velocities slightly greater. Hence, there are more particles losing energy to the wave than gaining from the wave, which leads to a resultant increase in the wave energy.

Physical interpretation

Mathematical theory of Landau damping is somewhat involved, see the section below. But there is a simple physical interpretation (although not strictly correct) that helps to visualize this phenomenon.

It is possible to imagine Langmuir waves as waves in the sea, and the particles as surfers trying to catch the wave, all moving in the same direction. If the surfer is moving on the water surface at a velocity slightly less than the waves he will eventually be caught and pushed along the wave (gaining energy), while a surfer moving slightly faster than a wave will be pushing on the wave as he moves uphill (losing energy to the wave).

It is worth noting that only the surfers are playing an important role in this energy interactions with the waves; a beachball floating on the water (zero velocity) will go up and down as the wave goes by, not gaining energy at all. Also, a boat that moves very fast (faster than the waves) does not exchange much energy with the wave.

Theoretical physics: perturbation theory

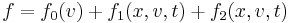

Theoretical treatment starts with Vlasov equation in the non-relativistic zero-magnetic field limit, Vlasov-Poisson set of equations. Explicit solutions are obtained in the limit of small  -field. The distribution function

-field. The distribution function  and field

and field  are expanded in series:

are expanded in series:  ,

,  and terms of equal order are collected.

and terms of equal order are collected.

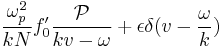

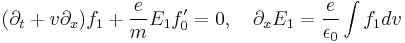

To first order the Vlasov-Poisson equations read

.

.

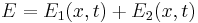

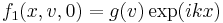

Landau calculated (see ref.[1]) the wave caused by an initial disturbance  and found by aid of Laplace transform and contour integration a damped travelling wave of the form

and found by aid of Laplace transform and contour integration a damped travelling wave of the form ![\exp[ik(x-v_{ph}t)-\gamma t]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/54efb193ff787f91f3f6fefb008e75ca.png) with wave number

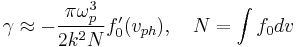

with wave number  and damping decrement

and damping decrement

.

.

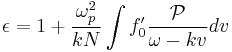

Here  is the plasma oscillation frequency and

is the plasma oscillation frequency and  is the electron density. Later Nico van Kampen proved[6] that the same result can be obtained with Fourier transform. He showed that the linearized Vlasov-Poisson equations have a continuous spectrum of singular normal modes, now known as van Kampen modes

is the electron density. Later Nico van Kampen proved[6] that the same result can be obtained with Fourier transform. He showed that the linearized Vlasov-Poisson equations have a continuous spectrum of singular normal modes, now known as van Kampen modes

in which  signifies principal value,

signifies principal value,  is the delta function (see generalized function) and

is the delta function (see generalized function) and

is the plasma permittivity. Decomposing the initial disturbance in these modes he obtained the Fourier spectrum of the resulting wave. Damping is explained by phase-mixing of these Fourier modes with slightly different frequencies near  .

.

It was not clear how damping could occur in a collisionless plasma: where does the wave energy go? In fluid theory, in which the plasma is modeled as a dispersive dielectric medium[7], the energy of Langmuir waves is known: field energy multiplied by the Brillouin factor  . But damping cannot be derived in this model. To calculate energy exchange of the wave with resonant electrons, Vlasov plasma theory has to be expanded to second order and problems about suitable initial conditions and secular terms arise.

. But damping cannot be derived in this model. To calculate energy exchange of the wave with resonant electrons, Vlasov plasma theory has to be expanded to second order and problems about suitable initial conditions and secular terms arise.

In [8] these problems are studied. Because calculations for an infinite wave are deficient in second order, a wave packet is analysed. Second-order initial conditions are found that suppress secular behavior and excite a wave packet of which the energy agrees with fluid theory. The figure shows the energy density of a wave packet traveling at the group velocity, its energy being carried away by electrons moving at the phase velocity. Total energy, the area under the curves, is conserved.

Mathematical theory: the Cauchy problem for perturbative solutions

The rigorous mathematical theory is based on solving the Cauchy problem for the evolution equation (here the partial differential Vlasov-Poisson equation) and proving estimates on the solution.

First a rather complete linearized mathematical theory has been developed since Landau.[9]

Going beyond the linearized equation and dealing with the nonlinearity has been a longstanding problem in the mathematical theory of Landau damping. Previously one mathematical result at the non-linear level was the existence of a class of exponentially damped solutions of the Vlasov-Poisson equation in a circle which had been proved in [10] by means of a scattering technique (this result has been recently extended in [11]). However these existence results do not say anything about which initial data could lead to such damped solutions.

In the recent paper[12] the initial data issue is solved and Landau damping is mathematically established for the first time for the non-linear Vlasov equation. It is proved that solutions starting in some neighborhood (for the analytic or Gevrey topology) of a linearly stable homogeneous stationary solution are (orbitally) stable for all times and are damped globally in time. The damping phenomenon is reinterpreted in terms of transfer of regularity of  as a function of

as a function of  and

and  , respectively, rather than exchanges of energy. Large scale variations pass into variations of smaller and smaller scale in velocity space, corresponding to a shift of the Fourier spectrum of

, respectively, rather than exchanges of energy. Large scale variations pass into variations of smaller and smaller scale in velocity space, corresponding to a shift of the Fourier spectrum of  as a function of

as a function of  . This shift, well known in linear theory, proves to hold in the non-linear case.

. This shift, well known in linear theory, proves to hold in the non-linear case.

See also

Notes and references

- ^ Landau, L. On the vibration of the electronic plasma. J. Phys. USSR 10 (1946), 25. English translation in JETP 16, 574. Reproduced in Collected papers of L.D. Landau, edited and with an introduction by D. ter Haar, Pergamon Press, 1965, pp. 445–460; and in Men of Physics: L.D. Landau, Vol. 2, Pergamon Press, D. ter Haar, ed. (1965).

- ^ Chen, Francis F. Introduction to Plasma Physics and Controlled Fusion. Second Ed., 1984 Plenum Press, New York.

- ^ Lynden-Bell, D. The stability and vibrations of a gas of stars. Mon. Not. R. astr. Soc. 124, 4 (1962), 279–296.

- ^ Binney, J., and Tremaine, S. Galactic Dynamics, second ed. Princeton Series in Astrophysics. Princeton University Press, 2008.

- ^ Tsurutani, B., and Lakhina, G. Some basic concepts of wave-particle interactions in collisionless plasmas. Reviews of Geophysics 35(4), p.491-502. Download

- ^ van Kampen, N.G., On the theory of stationary waves in plasma, Physica 21 (1955), 949–963. See http://theor.jinr.ru/~kuzemsky/kampenbio.html

- ^ Landau, L.D. and Lifshitz, E.M., Electrodynamics of continuous media §80, Pergamon Press (1984).

- ^ Best, Robert W.B., Energy and momentum density of a Landau-damped wave packet, J. Plasma Phys. 63 (2000), 371-391

- ^ See for instance Backus, G. Linearized plasma oscillations in arbitrary electron distributions. J. Math. Phys. 1 (1960), 178–191, 559. Degond, P. Spectral theory of the linearized Vlasov–Poisson equation. Trans. Amer. Math. Soc. 294, 2 (1986), 435–453. Maslov, V. P., and Fedoryuk, M. V. The linear theory of Landau damping. Mat. Sb. (N.S.) 127(169), 4 (1985), 445–475, 559.

- ^ Caglioti, E. and Maffei, C. "Time asymptotics for solutions of Vlasov-Poisson equation in a circle", J. Statist. Phys. 92, 1-2, 301-323 (1998)

- ^ Hwang, H. J. and Velasquez J. J. L. "On the Existence of Exponentially Decreasing Solutions of the Nonlinear Landau Damping Problem" preprint http://arxiv.org/abs/0810.3456

- ^ Mouhot, C., and Villani, C. On Landau damping, preprint http://fr.arxiv.org/abs/0904.2760 (quoted for the Fields Medal awarded to Cédric Villani in 2010)